I first met Jim sometime in late 1998 when I was invited by Lynn Cameron to a VWC board meeting at Ernie Dickerman’s place. My first impression of Jim was that he was a no-nonsense type of person. This fact was drilled home not too much later when I was elected as Secretary of the board, a position that I was ill equipped for. When I submitted the draft minutes to Jim for review, they came back bearing little resemblance to what I had committed to paper. After this failed first attempt, he more or less took over the role of secretary as well, much to my great relief.

In 2000, the Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition (SAFC), came to a VWC Board Meeting to announce that they had an open position for a field organizer. Jim and Bess encouraged me to apply. I did and was interviewed by the SAFC Executive Director that day. I was told thanks but no thanks. At the next break, Jim, Bess, and Bart Koehler asked that I be reconsidered for the position. I was reinterviewed and hired. To this day I have always felt a great deal of gratitude to Jim. Without his support, I would have missed out on this wonderful opportunity.

My task at SAFC was to create the necessary support for a bill on the ninth congressional district. Jim, Bess, and I drove to Radford on many occasions for what became known as the Radford Coalition. Jim was there when Smyth County passed our first resolution supporting wilderness. There is one event that I remember vividly about our efforts in Smyth County. I was driving home from a meeting with a county supervisor and overheard a conversation about a gathering at Hungry Mother State Park. I was tired and not looking forward to the long drive home. I decided to skip the meeting. As I was nearing Roanoke, I called Jim and mentioned this meeting. In that quiet no-nonsense way of his, he said, “Don’t you think you should turn around and go to the meeting?” Of course, I turned around. That meeting paved the way for the passage of the resolution. After the passage of the resolution in Craig County, Jim, Bess, and I chatted with a large contingent of bear hunters who were there to support our effort. When they left, Jim danced a little jig, smiled, and said, “I never thought I’d live to see the day when I had a pleasant conversation with bear hunters.”

As we worked through our discussion with the mountain bikers for the Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area proposal, Jim was there. During many tense meetings on forest planning with the George Washington Stakeholder group, Jim was there for many of the large group gatherings. As his health began to fail, Jim was less in

volved with the day-to-day operations of VWC, but he was always present in spirit.

Jim was an ever-present sounding board. He talked me back from jumping off many cliffs. His calm demeanor, steady hand, and sound advice helped to keep me grounded when the stress of the job was high. I, like so many others in the VWC family, will miss him greatly.

- Mark Miller, Executive Director, VWC

In 2000, the Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition (SAFC), came to a VWC Board Meeting to announce that they had an open position for a field organizer. Jim and Bess encouraged me to apply. I did and was interviewed by the SAFC Executive Director that day. I was told thanks but no thanks. At the next break, Jim, Bess, and Bart Koehler asked that I be reconsidered for the position. I was reinterviewed and hired. To this day I have always felt a great deal of gratitude to Jim. Without his support, I would have missed out on this wonderful opportunity.

My task at SAFC was to create the necessary support for a bill on the ninth congressional district. Jim, Bess, and I drove to Radford on many occasions for what became known as the Radford Coalition. Jim was there when Smyth County passed our first resolution supporting wilderness. There is one event that I remember vividly about our efforts in Smyth County. I was driving home from a meeting with a county supervisor and overheard a conversation about a gathering at Hungry Mother State Park. I was tired and not looking forward to the long drive home. I decided to skip the meeting. As I was nearing Roanoke, I called Jim and mentioned this meeting. In that quiet no-nonsense way of his, he said, “Don’t you think you should turn around and go to the meeting?” Of course, I turned around. That meeting paved the way for the passage of the resolution. After the passage of the resolution in Craig County, Jim, Bess, and I chatted with a large contingent of bear hunters who were there to support our effort. When they left, Jim danced a little jig, smiled, and said, “I never thought I’d live to see the day when I had a pleasant conversation with bear hunters.”

As we worked through our discussion with the mountain bikers for the Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area proposal, Jim was there. During many tense meetings on forest planning with the George Washington Stakeholder group, Jim was there for many of the large group gatherings. As his health began to fail, Jim was less in

volved with the day-to-day operations of VWC, but he was always present in spirit.

Jim was an ever-present sounding board. He talked me back from jumping off many cliffs. His calm demeanor, steady hand, and sound advice helped to keep me grounded when the stress of the job was high. I, like so many others in the VWC family, will miss him greatly.

- Mark Miller, Executive Director, VWC

I first met Jim Murray when I edited the Conservation Council of VA newsletter, 1973–76, while I was teaching high school in Richmond. I had studied English, French, German poetry at Oxford, 1969-70, so shared Oxford with Bess and Jim. When I spent summer of 76 at Mountain Lake Biology Station, studying Taxonomy of Seed Plants, in the field I learned British botanic pronunciations from Bess. I remember Doctor Murray climbing the brick arch of the lab building, with his long legs spread wide. Jim was still “Doctor Murray.” When Jim was sixty (because of oxygen-intake), he was mad that Nepal banned him from summitting a Himalayan mountain with his Oxford mates. After teaching as a Fulbright in Germany, I stayed with the Murrays at Bentivar (until I found a flat in town), as I started my Master’s in Environmental Sciences. I treasure memories of debates at the Murray dinner table. Two summers I housesat Bentivar’s gardens, dogs, chickens, calves, and wild critters while Bess and Jim were at Mt Lake. I had to scrub the kitchen ceiling when apple butter I was boiling spattered the ceiling. In Charlottesville, when I was grad student and also teaching Environmental Planning at UVa Engineering School, I wrote the resource inventory, management plan, and grant to buy Ivy Creek Natural Area from the Nature Conservancy; I set up the Ivy Creek Foundation (with Bess as board secretary) to ensure the City and County Parks managed the land for preservation and education. When I moved to Beaufort, NC, Bess became manager of Ivy Creek. When I had wrist surgery (from a climbing fall) at UVa hospital in 1979, three Murray kids all nursed me for five days, and Bess administered my Demerol painkiller every five hours.

During my doctorate in American literature, I spent another summer at Mt Lake, 1988, writing a novel about fighting a dam in Highland County that served as my dissertation, and I assisted researchers in their field work. Every summer for decades, I swam the mile-length of Mountain Lake. For decades, if I set up my tent, middle of the night, on Bentivar’s front hill above the floodplain by the confluence of North and South Forks of the Rivanna River, I was always welcome. Jim and Bess built a smaller house across the hill above the pond, and Tiki (back in town as French professor and dean at UVa) moved into the big house with her family—Stephen and Sophia; Joe, Andee, and daughters Maggie and Erin had built their house on another hill of Bentivar’s land. When I was lecturing in Virginia, I shared Jim’s 80-something birthday with the whole family, even Joe from California. Two years later, when Bess wrote me she was losing her memory, I walked Bentivar lanes and forded creeks with Jim. In 2017, I attended Bess’s Memorial at Ivy Creek; Joe and Will are as tall as their father. Four years ago, 2019, I drove Jim to the 40th anniversary of Ivy Creek and we walked paths through the meadows. Two years ago, 2021, when my goddaughter Kendall started her Master’s degree at Oxford in Biodiversity Conservation as a Rhodes Scholar, I telephoned Jim and Kendall talked with him on the phone. Today, October 2, 2023, Kendall started her DPhil at Oxford, in Biology like Jim, carrying on the heritage the Murrays instilled in me. - Susan Schmidt, friend of the Murrays

During my doctorate in American literature, I spent another summer at Mt Lake, 1988, writing a novel about fighting a dam in Highland County that served as my dissertation, and I assisted researchers in their field work. Every summer for decades, I swam the mile-length of Mountain Lake. For decades, if I set up my tent, middle of the night, on Bentivar’s front hill above the floodplain by the confluence of North and South Forks of the Rivanna River, I was always welcome. Jim and Bess built a smaller house across the hill above the pond, and Tiki (back in town as French professor and dean at UVa) moved into the big house with her family—Stephen and Sophia; Joe, Andee, and daughters Maggie and Erin had built their house on another hill of Bentivar’s land. When I was lecturing in Virginia, I shared Jim’s 80-something birthday with the whole family, even Joe from California. Two years later, when Bess wrote me she was losing her memory, I walked Bentivar lanes and forded creeks with Jim. In 2017, I attended Bess’s Memorial at Ivy Creek; Joe and Will are as tall as their father. Four years ago, 2019, I drove Jim to the 40th anniversary of Ivy Creek and we walked paths through the meadows. Two years ago, 2021, when my goddaughter Kendall started her Master’s degree at Oxford in Biodiversity Conservation as a Rhodes Scholar, I telephoned Jim and Kendall talked with him on the phone. Today, October 2, 2023, Kendall started her DPhil at Oxford, in Biology like Jim, carrying on the heritage the Murrays instilled in me. - Susan Schmidt, friend of the Murrays

It was a privilege to land in one of Jim Murray’s orbits. I always felt an unspoken bond over our Virginia roots, in addition to the unequivocal commitment to trying to legislate protections for wherever that possibility exists. My fondest memories of Jim include his irreverent commentary on bureaucratic speechifying—pithy and spoken in undertones just loud enough to cause his neighbor to struggle to suppress laughter. When I think of Jim, I think of how comfortable it felt to be around a person so highly entertained by humanity. He had no tolerance for any hint of pomposity—-my experience included the relentless deletion of any hint of flowery language in the letters I wrote on behalf of VWC. Jim’s red pen was famous. Less is more—a Jim truism. I loved his minimalism-his brown bag lunches and suppers of a sandwich and fruit, his vehicles, his comments. I miss him, his deep respect for the critters, his delight at any Wilderness good news, his stamina for soldiering on, and encouraging the rest of us to do so as well.

- Laura Neale, board member and past-president, VWC

- Laura Neale, board member and past-president, VWC

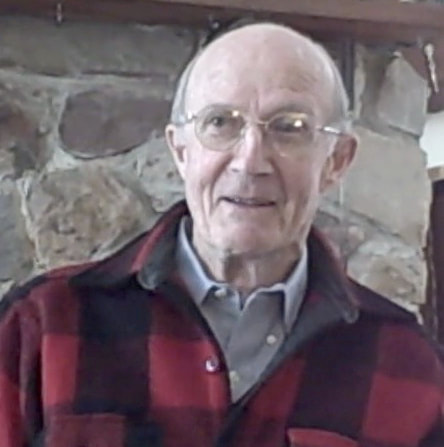

I met Jim Murray when I went to my first VWC meeting in the Ivy Creek Nature Center barn in the mid-1980s. Jim was sitting quietly among the gathering of faithful wilderness advocates. I can’t remember the topics discussed that day, but I do remember that Jim was never the first to speak in a discussion. When he had something to say, he said it quietly, eloquently, and succinctly. When Jim Murray spoke, everybody listened. I marveled at his breadth of knowledge and his wisdom. He was clearly respected by all, including Ernie Dickerman. Together Jim and Ernie were the guiding force behind the VWC’s efforts to protect wilderness.

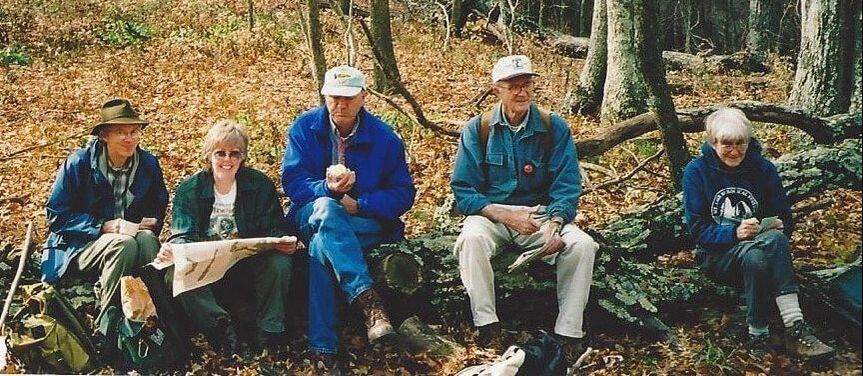

The Forest Service was starting to work on a new Forest Plan for the GWNF in the late 1980s. VWC played a vital role in identifying the best candidates for Wilderness designation. Back in those days, VWC went on scouting trips to check out Wilderness candidates. Malcolm and I went on many of these with Jim and Bess, often accompanied by a dog or two. We were not wedded to following trails and often took shortcuts that required bushwhacking through mountain laurel. Jim never got lost because he had already spent considerable time getting to know the areas, mostly through hunting, hiking, and studying nature. The dogs sometimes did get lost, but we always found them – eventually. One of their beagles took off from a camp at Laurel Fork where VWC was meeting. Who knows where a beagle following its nose will end up, especially in a 10,000-acre roadless area surrounded by a vast, undeveloped forest. Jim and Bess jumped in their car and took off to head the beagle off. They returned in about an hour with the errant beagle in tow.

Jim had a special appreciation for Laurel Fork and Little River and worked tirelessly for both. He was involved in the difficult negotiations with the mountain bike community in 2002-04 that resulted in the Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area proposal. The day we all came to agreement on a proposal, Jim, who was usually reserved, surprised us all by dancing an Irish jig right there in the Massanutten Public Library.

As I got to know Jim, I began to realize how extensive his knowledge and experience were and how deeply he was committed to preserving wilderness. Jim was a gifted speaker and writer and had a keen mind. He could always get to the heart of the matter and offer sound advice. I can’t count the times he helped VWC find clarity on difficult issues.

In my eyes, Jim was a giant, but he treated me as an equal and was very supportive. Jim and Bess would do anything that was needed for Wilderness. Together they tended to the Wilderness flock by feeding us, hosting VWC meetings at Bentivar, hosting U.S. Representatives on hikes into proposed Wilderness, and attending everything from Congressional hearings to Forest Service meetings. Jim was reliable and rock solid. As a full Professor of Biology at UVA, he was widely respected by academics across Virginia and around the world. Though he studied snails, he knew birds, butterflies, salamanders, wildflowers, forest ecology, geology, and much more. He kept his childlike fascination for nature throughout his life. Jim and Bess together were a powerhouse of knowledge, and they used their gifts every day to preserve Wilderness. Those of us who were lucky enough to know them will continue to be enriched and motivated by their passionate commitment.

– Lynn Cameron, board member and past-president, VWC

The Forest Service was starting to work on a new Forest Plan for the GWNF in the late 1980s. VWC played a vital role in identifying the best candidates for Wilderness designation. Back in those days, VWC went on scouting trips to check out Wilderness candidates. Malcolm and I went on many of these with Jim and Bess, often accompanied by a dog or two. We were not wedded to following trails and often took shortcuts that required bushwhacking through mountain laurel. Jim never got lost because he had already spent considerable time getting to know the areas, mostly through hunting, hiking, and studying nature. The dogs sometimes did get lost, but we always found them – eventually. One of their beagles took off from a camp at Laurel Fork where VWC was meeting. Who knows where a beagle following its nose will end up, especially in a 10,000-acre roadless area surrounded by a vast, undeveloped forest. Jim and Bess jumped in their car and took off to head the beagle off. They returned in about an hour with the errant beagle in tow.

Jim had a special appreciation for Laurel Fork and Little River and worked tirelessly for both. He was involved in the difficult negotiations with the mountain bike community in 2002-04 that resulted in the Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area proposal. The day we all came to agreement on a proposal, Jim, who was usually reserved, surprised us all by dancing an Irish jig right there in the Massanutten Public Library.

As I got to know Jim, I began to realize how extensive his knowledge and experience were and how deeply he was committed to preserving wilderness. Jim was a gifted speaker and writer and had a keen mind. He could always get to the heart of the matter and offer sound advice. I can’t count the times he helped VWC find clarity on difficult issues.

In my eyes, Jim was a giant, but he treated me as an equal and was very supportive. Jim and Bess would do anything that was needed for Wilderness. Together they tended to the Wilderness flock by feeding us, hosting VWC meetings at Bentivar, hosting U.S. Representatives on hikes into proposed Wilderness, and attending everything from Congressional hearings to Forest Service meetings. Jim was reliable and rock solid. As a full Professor of Biology at UVA, he was widely respected by academics across Virginia and around the world. Though he studied snails, he knew birds, butterflies, salamanders, wildflowers, forest ecology, geology, and much more. He kept his childlike fascination for nature throughout his life. Jim and Bess together were a powerhouse of knowledge, and they used their gifts every day to preserve Wilderness. Those of us who were lucky enough to know them will continue to be enriched and motivated by their passionate commitment.

– Lynn Cameron, board member and past-president, VWC

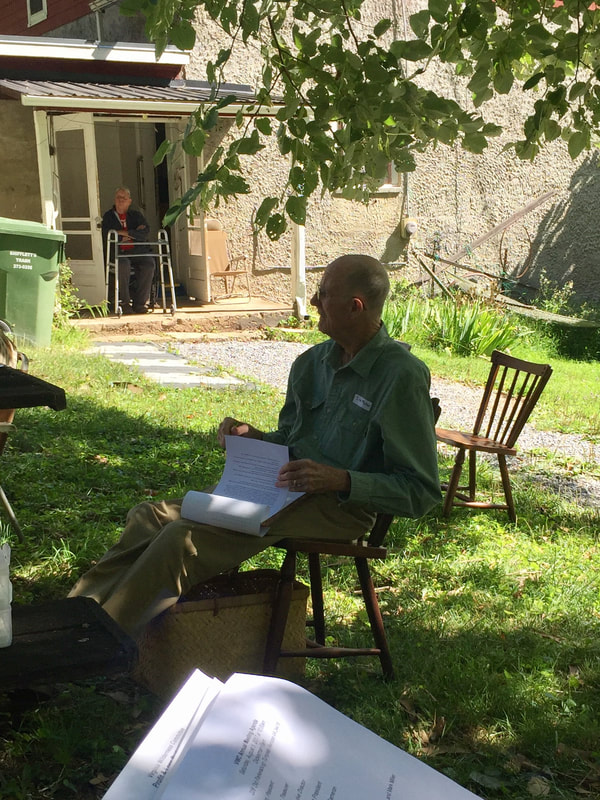

When I was asked to write a short article about Jim Murray, it gave me an opportunity to explore the great success of the Virginia Wilderness Committee. The Wilderness history of the Virginia Wilderness Committee is the Wilderness history of Jim Murray. But, it is also a story with many other important people: Ernie Dickerman, Mark Miller, John Warner, Rick Boucher. It is important to note that in 2019, when the Virginia Wilderness Committee celebrated its 50th anniversary, Jim Murray received its Lifetime Achievement Award.

It is not surprising that Jim Murray was honored with a lifetime achievement award. He was a biologist, a serious biologist, at one time Director of the Mountain Lake Biological Station and chaired the Department of Biology at UVA. He went to Davidson College and was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University where he later received a doctorate in Zoology. He began teaching at the University of Virginia in 1962. In addition to his scholarship, he was an outdoorsman, a climber, hiker, and lifelong conservationist. And, he was a passionate advocate, effective organizer, and outstanding leader. Maybe, the most important contribution was having his wife, Bess, as a partner through all the Wilderness campaigns.

Ernie Dickerman introduced me to Bess and Jim in 1998 a few months before Ernie's death. Ernie worked with The Wilderness Society for many years and was perhaps the most important advocate for the Eastern Areas Wilderness Act of 1975. I met Ernie in the 1970s when I was active with the Tennessee Sierra Club, and we, too, were working on the Eastern Areas Wilderness Act. Ernie was delighted when a regional conservation friend was chosen to be head of The Wilderness Society. He knew that it would not be hard to convince me to support Wilderness work in Virginia. Early in my conservation career, I learned the importance of organizing at the local level. Ernie Dickerman underscored that priority, and Jim and Bess Murray practiced it. Wilderness is the ultimate expression of conservation, but that expression requires a political strategy. Jim worked effectively with Congressmen Rick Boucher and Jim Olin, as well as Senator John Warner to build political support for Wilderness campaigns. Jim and Bess were very effective in organizing the Virginia Wilderness Committee and also building a Wilderness coalition with The Wilderness Society, the Sierra Club, and the Southern Environmental Law Center.

It is important to note that in the same way that Ernie Dickerman was a valued advisor for Jim's early work on Wilderness, Mark Miller became a valued partner throughout their tenure together with the Virginia Wilderness Committee. Mark shared Jim's passion for Wilderness and also understood the only way to preserve Wilderness is by building effective support at the local level.

When I look at the many Wilderness campaigns in Virginia since 1969, the founding of the Virginia Wilderness Committee, and studied how Virginia now has an impressive 217,000 acres of Wilderness in the state, I see Jim Murray behind it all - the Eastern Areas Wilderness Act; 80,000 acres of Wilderness in the Shenandoah National Park; the passage of the Virginia Wilderness Acts of 1984, 1988, 2000, and 2009; and the creation of the Mount Pleasant National Scenic Areas Act of 1994.

Jim's work continues. In fact, the Virginia Wilderness Committee is working to include major additions to Wilderness in the Farm Bill that we hope will pass this year.

Much of my life, certainly the nearly two decades with The Wilderness Society, has been devoted to building local political support for conservation and environmental policy. When I think of the effective groups with which I have worked, the Virginia Wilderness Committee is at the top of the list. As always, an organization's effectiveness is the major byproduct of good leadership. Virginia, the Wilderness community, and our earth have benefited from the outstanding leadership of Jim Murray. It has been an honor to have been able to work with him.

- Bill Meadows, The Wilderness Society

It is not surprising that Jim Murray was honored with a lifetime achievement award. He was a biologist, a serious biologist, at one time Director of the Mountain Lake Biological Station and chaired the Department of Biology at UVA. He went to Davidson College and was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University where he later received a doctorate in Zoology. He began teaching at the University of Virginia in 1962. In addition to his scholarship, he was an outdoorsman, a climber, hiker, and lifelong conservationist. And, he was a passionate advocate, effective organizer, and outstanding leader. Maybe, the most important contribution was having his wife, Bess, as a partner through all the Wilderness campaigns.

Ernie Dickerman introduced me to Bess and Jim in 1998 a few months before Ernie's death. Ernie worked with The Wilderness Society for many years and was perhaps the most important advocate for the Eastern Areas Wilderness Act of 1975. I met Ernie in the 1970s when I was active with the Tennessee Sierra Club, and we, too, were working on the Eastern Areas Wilderness Act. Ernie was delighted when a regional conservation friend was chosen to be head of The Wilderness Society. He knew that it would not be hard to convince me to support Wilderness work in Virginia. Early in my conservation career, I learned the importance of organizing at the local level. Ernie Dickerman underscored that priority, and Jim and Bess Murray practiced it. Wilderness is the ultimate expression of conservation, but that expression requires a political strategy. Jim worked effectively with Congressmen Rick Boucher and Jim Olin, as well as Senator John Warner to build political support for Wilderness campaigns. Jim and Bess were very effective in organizing the Virginia Wilderness Committee and also building a Wilderness coalition with The Wilderness Society, the Sierra Club, and the Southern Environmental Law Center.

It is important to note that in the same way that Ernie Dickerman was a valued advisor for Jim's early work on Wilderness, Mark Miller became a valued partner throughout their tenure together with the Virginia Wilderness Committee. Mark shared Jim's passion for Wilderness and also understood the only way to preserve Wilderness is by building effective support at the local level.

When I look at the many Wilderness campaigns in Virginia since 1969, the founding of the Virginia Wilderness Committee, and studied how Virginia now has an impressive 217,000 acres of Wilderness in the state, I see Jim Murray behind it all - the Eastern Areas Wilderness Act; 80,000 acres of Wilderness in the Shenandoah National Park; the passage of the Virginia Wilderness Acts of 1984, 1988, 2000, and 2009; and the creation of the Mount Pleasant National Scenic Areas Act of 1994.

Jim's work continues. In fact, the Virginia Wilderness Committee is working to include major additions to Wilderness in the Farm Bill that we hope will pass this year.

Much of my life, certainly the nearly two decades with The Wilderness Society, has been devoted to building local political support for conservation and environmental policy. When I think of the effective groups with which I have worked, the Virginia Wilderness Committee is at the top of the list. As always, an organization's effectiveness is the major byproduct of good leadership. Virginia, the Wilderness community, and our earth have benefited from the outstanding leadership of Jim Murray. It has been an honor to have been able to work with him.

- Bill Meadows, The Wilderness Society

Memorial contributions may be sent to:

Donate/Join - Virginia Wilderness Committee (vawilderness.org)

Virginia Wilderness Committee

PO Box 1235, Lexington, VA 24450

Donate/Join - Virginia Wilderness Committee (vawilderness.org)

Virginia Wilderness Committee

PO Box 1235, Lexington, VA 24450

RSS Feed

RSS Feed