End of Year Newsletter, 2023

From the President

As the Virginia Wilderness Committee (VWC) moves into its next year, we may see the successful completion of our two big campaigns, protecting the 92,000 acres Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area with the Shenandoah Mountain Act and the Lower Cowpasture project with the Virginia Wilderness Additions Act, adding nearly 34,000 acres to the Wilderness Preservation System. This will complete two major chapters in our organization’s fifty-four-year history. When this legislation is enacted, VWC will begin its next chapter, which we have already started working towards. To accomplish this goal, VWC has undertaken a strategic planning process. With the assistance of Dr. Rob Alexander, Associate Professor of Political Science at JMU, the board held its first planning meeting. A wide array of issues was discussed at this first meeting, and the board strongly supports continued efforts to protect Virginia’s public lands. While no decisions have been made, we look forward to sharing with you our vision for the organization’s future.

Another major change we will see in the coming year is the hiring of a new Executive Director. Mark Miller has been with VWC since 1998 when he was first elected to the board. Mark served as Secretary on the board for a couple of years. From 2000 until 2011 he served as Vice President while working for the Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition (SAFC). During that time, he traveled around southwest Virginia working to advance what became known as the Ridge and Valley Act. He was a founding member of the Stakeholder Collaborative for the George Washington National Forest. When SAFC closed its doors, VWC hired Mark as the Field Director. It became apparent that his position was much larger than just a Field Director and Mark was elevated to VWC’s first Executive Director. Mark plans to step back from that role later this year. At the Annual Meeting, the board put together a hiring committee which has been very busy. We hope to announce our new Executive Director in the not-too-distant future. Mark will not be leaving VWC, he will return to his position as Field Director in a part-time capacity.

Another major change VWC witnessed is the passing of Jim Murray. Jim was one of the original founders of VWC and served on the board for nearly fifty-five years. Jim served two stints as President. He was our resident historian and the glue that held the organization together. He was steadfast in his belief in the importance of wilderness protection. With his guidance and leadership, he has left VWC in a strong position to continue our advocacy work to permanently protect Virginia’s public lands.

Finally, we could not do this work without your financial support. During our transition your support is especially important, as it will allow us to bring on a new Executive Director and expand our ability to undertake new campaigns providing additional protection for our public lands in the future.

Sincerely,

John D. Hutchinson V, VWC President

Another major change we will see in the coming year is the hiring of a new Executive Director. Mark Miller has been with VWC since 1998 when he was first elected to the board. Mark served as Secretary on the board for a couple of years. From 2000 until 2011 he served as Vice President while working for the Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition (SAFC). During that time, he traveled around southwest Virginia working to advance what became known as the Ridge and Valley Act. He was a founding member of the Stakeholder Collaborative for the George Washington National Forest. When SAFC closed its doors, VWC hired Mark as the Field Director. It became apparent that his position was much larger than just a Field Director and Mark was elevated to VWC’s first Executive Director. Mark plans to step back from that role later this year. At the Annual Meeting, the board put together a hiring committee which has been very busy. We hope to announce our new Executive Director in the not-too-distant future. Mark will not be leaving VWC, he will return to his position as Field Director in a part-time capacity.

Another major change VWC witnessed is the passing of Jim Murray. Jim was one of the original founders of VWC and served on the board for nearly fifty-five years. Jim served two stints as President. He was our resident historian and the glue that held the organization together. He was steadfast in his belief in the importance of wilderness protection. With his guidance and leadership, he has left VWC in a strong position to continue our advocacy work to permanently protect Virginia’s public lands.

Finally, we could not do this work without your financial support. During our transition your support is especially important, as it will allow us to bring on a new Executive Director and expand our ability to undertake new campaigns providing additional protection for our public lands in the future.

Sincerely,

John D. Hutchinson V, VWC President

Wildlife Photographer of the Year Honoree – Steven David Johnson

A photograph taken in a pond on the property of Lynn and Malcolm Cameron sent Steven David Johnson, conservation photographer, VWC board Vice President, and Eastern Mennonite University professor, to be honored at the Wildlife Photographer of the Year event at the Natural History Museum in London, England this fall. His photograph, "Pool of Wonder," is one of 100 images featured in this year's exhibit. Here is a description of the photograph, seen below:

Female spotted salamanders deposit their eggs in luminous clusters just below the surface of the water. These masses often stand out in extraordinary relief from the background of moss or leaves. The spotted salamander egg masses found in vernal pools are otherworldly in their abstract beauty. When illuminated directly, they appear as tiny worlds edged with delicate blue halos.

The vernal pools of Appalachia form from seasonal rains and snowmelt. These temporary bodies of water are ideal environments for egg-laying since they are free from most predator fish. In late winter and early spring, these pools host breeding events for amphibians and macroinvertebrates.

There are numerous threats to vernal pools and other forest wetland environments including land development, roads, fossil fuel infrastructure, the global spread of amphibian diseases (such as chytrid and Bsal), and climate change.

This same photograph was featured on the cover of The Nature Conservancy magazine in 2021 and included in a recent National Geographic article.

“As a conservation photographer, I’m drawn to the intricate dance of underwater life in Appalachian Mountain forests and nearby lowlands,” shared Steve.

Steve is generous with his work and his photographs are frequently used by VWC in our campaigns and communications. His stunning photography creates a narrative for nature and the work of conservation. We congratulate him on this well-deserved recognition. To see all of the photos in the exhibit, go to www.nhm.ac.uk/wpy/gallery. To learn more about Steve’s work and vernal pools, go to stevendavidjohnson.com.

Female spotted salamanders deposit their eggs in luminous clusters just below the surface of the water. These masses often stand out in extraordinary relief from the background of moss or leaves. The spotted salamander egg masses found in vernal pools are otherworldly in their abstract beauty. When illuminated directly, they appear as tiny worlds edged with delicate blue halos.

The vernal pools of Appalachia form from seasonal rains and snowmelt. These temporary bodies of water are ideal environments for egg-laying since they are free from most predator fish. In late winter and early spring, these pools host breeding events for amphibians and macroinvertebrates.

There are numerous threats to vernal pools and other forest wetland environments including land development, roads, fossil fuel infrastructure, the global spread of amphibian diseases (such as chytrid and Bsal), and climate change.

This same photograph was featured on the cover of The Nature Conservancy magazine in 2021 and included in a recent National Geographic article.

“As a conservation photographer, I’m drawn to the intricate dance of underwater life in Appalachian Mountain forests and nearby lowlands,” shared Steve.

Steve is generous with his work and his photographs are frequently used by VWC in our campaigns and communications. His stunning photography creates a narrative for nature and the work of conservation. We congratulate him on this well-deserved recognition. To see all of the photos in the exhibit, go to www.nhm.ac.uk/wpy/gallery. To learn more about Steve’s work and vernal pools, go to stevendavidjohnson.com.

New Partnerships

At the end of 2022, the Virginia Native Plant Society (VNPS) offered to partner with the Virginia Wilderness Committee (VWC) in our goal of purchasing the outstanding mineral rights under the proposed Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area (SMNSA). Although the U.S. Forest Service owns this land, private individuals and companies own the underground mineral rights and can develop and extract those minerals. As long as there is the possibility of development and mining, the Forest Service will not support a designation of Wilderness. VWC thinks permanently protecting these special places as Wilderness is important and to do so it is necessary to obtain the mineral rights from these private owners.

The financial assistance of VNPS has made our goal attainable. In April, members of VNPS generously gave $48,771.74 to this effort. VWC is still in discussions with Norfolk Southern to finalize the contract for a tract under the proposed Little River Wilderness within the SMNSA but we are now able to make the purchase once the contracts have been finalized. Next, VWC will move forward with the purchase of the mineral rights under the proposed Lynn Hollow Wilderness.

Executive Director Mark Miller had the opportunity to thank members of the VNPS-Jefferson Chapter for their role in this generous donation at their meeting in Charlottesville in April. VWC is grateful for their support and this new partnership.

The financial assistance of VNPS has made our goal attainable. In April, members of VNPS generously gave $48,771.74 to this effort. VWC is still in discussions with Norfolk Southern to finalize the contract for a tract under the proposed Little River Wilderness within the SMNSA but we are now able to make the purchase once the contracts have been finalized. Next, VWC will move forward with the purchase of the mineral rights under the proposed Lynn Hollow Wilderness.

Executive Director Mark Miller had the opportunity to thank members of the VNPS-Jefferson Chapter for their role in this generous donation at their meeting in Charlottesville in April. VWC is grateful for their support and this new partnership.

Forest Protection Updates

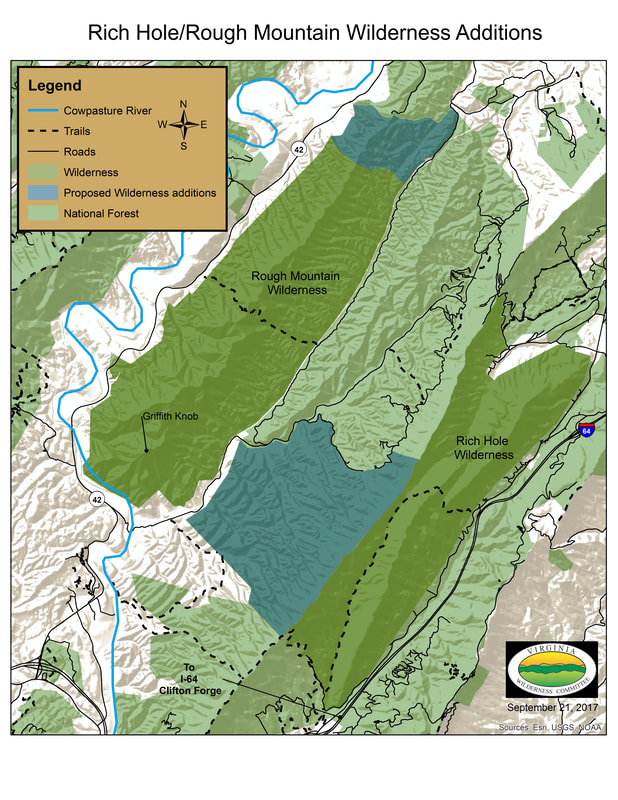

If it feels like we have been talking about our bills in Congress for several years, it is because we have! Both the Virginia Wilderness Additions Act, legislation that would add a total of 5,600 acres to the existing Rough Mountain and Rich Hole Wilderness areas and the Shenandoah Mountain Act, legislation to establish the Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area with embedded Wilderness, were reintroduced in the Senate this year, in March and July, respectively. However, neither of these bills has moved. This does not mean we have been stagnant, as you will read below. We have received word both bills will be included in the Senate version of the 2023 Farm Bill and hope to see them in the House version as well. We believe a celebration will be in order in 2024.

After

completing the purchase of the first tract of mineral rights under the proposed Little River Wilderness, we are awaiting a purchase agreement from Norfolk Southern for the second tract of mineral rights. As with awaiting bill passage in Congress, this also takes time, persistence, and a lot of patience. When the agreement arrives, thanks to the generous support from our members, the Virginia Native Plant Society, and The Wilderness Society, we already have the funds in hand to complete the purchase. With this second tract we will have nearly eliminated the threat of privately held mineral rights under the Little River proposal halting a Wilderness designation.

This summer, VWC was asked by the U.S. Forest Service to help with the acquisition of a ten-acre tract of land that is bounded on three sides by The Priest Wilderness, in Amherst County. We reached out to the Wilderness Land Trust for assistance with the purchase. The Wilderness Land Trust recently completed an appraisal of the property and is now working to raise the money needed to acquire the property. Because this land is adjacent to The Priest Wilderness, once it has been deeded over to the Forest Service it can immediately be considered as an addition to The Priest Wilderness. Due to language in the Wilderness Act, this tract does not require an Act of Congress to become part of the Wilderness, it only needs a signature from the Secretary of Agriculture. As the Forest Service is supportive of the effort to acquire this small tract of land; we expect to see another ten acres added to The Priest soon.

After

completing the purchase of the first tract of mineral rights under the proposed Little River Wilderness, we are awaiting a purchase agreement from Norfolk Southern for the second tract of mineral rights. As with awaiting bill passage in Congress, this also takes time, persistence, and a lot of patience. When the agreement arrives, thanks to the generous support from our members, the Virginia Native Plant Society, and The Wilderness Society, we already have the funds in hand to complete the purchase. With this second tract we will have nearly eliminated the threat of privately held mineral rights under the Little River proposal halting a Wilderness designation.

This summer, VWC was asked by the U.S. Forest Service to help with the acquisition of a ten-acre tract of land that is bounded on three sides by The Priest Wilderness, in Amherst County. We reached out to the Wilderness Land Trust for assistance with the purchase. The Wilderness Land Trust recently completed an appraisal of the property and is now working to raise the money needed to acquire the property. Because this land is adjacent to The Priest Wilderness, once it has been deeded over to the Forest Service it can immediately be considered as an addition to The Priest Wilderness. Due to language in the Wilderness Act, this tract does not require an Act of Congress to become part of the Wilderness, it only needs a signature from the Secretary of Agriculture. As the Forest Service is supportive of the effort to acquire this small tract of land; we expect to see another ten acres added to The Priest soon.

Outreach

Here at the Virginia Wilderness Committee (VWC), we love to get the word out about Wilderness in Virginia; where to find it and why we need it. If you have a group that would like to hear a presentation about Wilderness or our campaigns, please contact us. If you have an event at which you think VWC would fit as an exhibitor or presenter, give us a call. If your group would like to be led on a walk/hike in Wilderness or on our federal public lands, we would love to go out with you. If you have taken photographs of Virginia Wilderness you would like to share, please let us highlight them. We want to continue to foster understanding and appreciation of Wilderness, and also promote enjoyment of our public lands. You can ensure that we are able to do this.

Contact: Lacey Dean, Education & Outreach Coordinator, [email protected]

Contact: Lacey Dean, Education & Outreach Coordinator, [email protected]

Jefferson Mountain Treasures

VWC’s Executive Director Mark Miller has been traveling across the Jefferson National Forest recently, hiking the many Virginia Mountain Treasures on the forest. The current Treasures book for the Jefferson National Forest is over 20 years old. Due to the Ridge and Valley Act, road closures, and other changes on the forest, it was time for an update. We hope to have the new Jefferson Mountain Treasures completed by next summer.

Stewardship of Protected Places: A Shenandoah Mountain Story

by Lynn Cameron, Co-Chair, Friends of Shenandoah Mountain

The hope of the Virginia Wilderness Committee (VWC) is that the Shenandoah Mountain Act, which was reintroduced by Senators Kaine and Warner in July, will offer lasting protection of a 92,562-acre tract of some of Virginia’s most outstanding, unfragmented forest on federal land. Wilderness and National Scenic Area designation will protect this area, which lies within a Biodiversity Hotspot identified by The Nature Conservancy, from commercial energy development, logging, and new roads. When the bill is finally passed and signed into law this year or next, we will celebrate a major victory. It would be easy to check off “Protection of Shenandoah Mountain” from our to-do list. Unfortunately, protecting the biodiversity and natural characteristics of the Shenandoah Mountain area and other special wild areas will not be finished when the area is designated by Congress. Stewardship is an ongoing responsibility for all of us who care about protecting our favorite wild places.

The soon-to-be designated Shenandoah Mountain area and all the existing Wilderness and National Scenic Areas in Virginia are facing new threats that will require collective efforts by people and organizations who care about Wilderness. Among these new threats are climate change, non-native invasive species (NNIS), and overuse. This summer, on Shenandoah Mountain, a group of local people banded together to provide critical stewardship of this special place.

It all began when a hiker discovered a patch of the fast-growing invasive Mile-a-Minute weed (MM), Persicaria perfoliate, on the southern edge of the proposed Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area (SMNSA) last fall. This multi-acre patch was exploding on both sides of the Wild Oak National Recreation Trail near Elkhorn Lake. As far as we know, this is the first occurrence of MM in the Shenandoah Mountain area.

This discovery was alarming because MM (known as “Kudzu of the North”) can grow up to 26 feet in a year, killing trees and smothering out native biodiversity. The little blue seeds can be carried to new locations by hiking boots, bike tires, birds, and animals and can be washed miles downstream where they start new infestations.

Friends of Shenandoah Mountain (FOSM) considered this new invasive to be a red alert threat that required fast action. Our first steps were 1) to reach out to GW/Jeff National Forest North Zone biologist and 2) to assess the size and location of the patch. It was a 4-mile hike from a trailhead, and the Forest Service access road was washed out and impassable. We reached out to a Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC) GPS Ranger who made a shape file of the patch. Another volunteer used his drone for arial shots. We also reached out to Blue Ridge PRISM to find out what we could do to remove the patch, as well as how and when. Timing is everything with invasive plant removal. We joined forces with several nature-oriented and trail organizations, including Virginia Native Plant Society (Shenandoah Chapter), Headwaters Master Naturalists, and PATC, and decided to pull the MM in early June, after the Forest Service (FS) applied a preemergent spray to keep seeds from germinating. The FS repaired the road to make vehicle transport of volunteers possible. After publicizing the MM pull through social media, email lists, and posters, we were able to gather 35 volunteers who mobilized up to the patch on June 3. Though the patch had been sprayed a few weeks earlier, we found plenty of young vines to pull - tens of thousands. The volunteers rolled up their sleeves and made their way into the dense thicket of vines. As I looked down the steep embankment from the Forest Road, I saw sunhats, backs bent over and gloved hands pulling one vine after another as fast as hands could move. We gathered in a circle for lunch, shared our experiences with the barbed vines, and then went back to pull some more. By midafternoon, we felt like we had done a thorough job. Still, we wondered if the seed bank had more seeds that would germinate later in the summer or even next year. We celebrated the success of a big turnout and a strong effort, but realized that only time would tell if our effort was effective in eradicating MM.

In early October, we returned to the site to see if new vines had germinated or if plants we missed had grown and produced seed. We scoured the patch for 2 hours and found a mere handful of MM vines and only two mature blue berry-like seeds. Perhaps some of the weak, shallow roots of any remaining MM had succumbed to the severe drought in the Shenandoah Valley this summer and fall. One thing is for sure – the combined effort of participating groups in collaboration with the FS resulted in almost completely wiping out a major threat to forest health and biodiversity of the proposed SMNSA.

FOSM and our partners will monitor this site in the spring to see if new MM shoots are emerging. If we find any, we will organize a small group to take care of them. We now have 35 volunteers who can easily recognize it. We hope our continued monitoring and pulling will eventually eradicate MM from the Shenandoah Mountain area.

We are also seeing occurrences of Garlic mustard, Japanese stiltgrass, Ailanthus, Oriental lady’s thumb, and one small patch of Wavyleaf basketgrass along trails in the proposed SMNSA. PATC volunteers are increasingly incorporating control of non-native invasive plants into their trail maintenance and have attacked several of these unwanted plants. Trail maintainers are in a good position to identify new populations of NNIS and control them while they are still small.

Many of these NNIS are spread by trail users. Hikers, backpackers, trail maintainers, naturalists, hunters, and fishermen can all play a role in protecting our Wilderness and National Scenic Areas by observing, reporting, and banding together to be stewards of our protected areas, the very richest repositories of nature itself, so that Virginia’s tremendous biodiversity can thrive, and future generations can enjoy it as we have.

The soon-to-be designated Shenandoah Mountain area and all the existing Wilderness and National Scenic Areas in Virginia are facing new threats that will require collective efforts by people and organizations who care about Wilderness. Among these new threats are climate change, non-native invasive species (NNIS), and overuse. This summer, on Shenandoah Mountain, a group of local people banded together to provide critical stewardship of this special place.

It all began when a hiker discovered a patch of the fast-growing invasive Mile-a-Minute weed (MM), Persicaria perfoliate, on the southern edge of the proposed Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area (SMNSA) last fall. This multi-acre patch was exploding on both sides of the Wild Oak National Recreation Trail near Elkhorn Lake. As far as we know, this is the first occurrence of MM in the Shenandoah Mountain area.

This discovery was alarming because MM (known as “Kudzu of the North”) can grow up to 26 feet in a year, killing trees and smothering out native biodiversity. The little blue seeds can be carried to new locations by hiking boots, bike tires, birds, and animals and can be washed miles downstream where they start new infestations.

Friends of Shenandoah Mountain (FOSM) considered this new invasive to be a red alert threat that required fast action. Our first steps were 1) to reach out to GW/Jeff National Forest North Zone biologist and 2) to assess the size and location of the patch. It was a 4-mile hike from a trailhead, and the Forest Service access road was washed out and impassable. We reached out to a Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC) GPS Ranger who made a shape file of the patch. Another volunteer used his drone for arial shots. We also reached out to Blue Ridge PRISM to find out what we could do to remove the patch, as well as how and when. Timing is everything with invasive plant removal. We joined forces with several nature-oriented and trail organizations, including Virginia Native Plant Society (Shenandoah Chapter), Headwaters Master Naturalists, and PATC, and decided to pull the MM in early June, after the Forest Service (FS) applied a preemergent spray to keep seeds from germinating. The FS repaired the road to make vehicle transport of volunteers possible. After publicizing the MM pull through social media, email lists, and posters, we were able to gather 35 volunteers who mobilized up to the patch on June 3. Though the patch had been sprayed a few weeks earlier, we found plenty of young vines to pull - tens of thousands. The volunteers rolled up their sleeves and made their way into the dense thicket of vines. As I looked down the steep embankment from the Forest Road, I saw sunhats, backs bent over and gloved hands pulling one vine after another as fast as hands could move. We gathered in a circle for lunch, shared our experiences with the barbed vines, and then went back to pull some more. By midafternoon, we felt like we had done a thorough job. Still, we wondered if the seed bank had more seeds that would germinate later in the summer or even next year. We celebrated the success of a big turnout and a strong effort, but realized that only time would tell if our effort was effective in eradicating MM.

In early October, we returned to the site to see if new vines had germinated or if plants we missed had grown and produced seed. We scoured the patch for 2 hours and found a mere handful of MM vines and only two mature blue berry-like seeds. Perhaps some of the weak, shallow roots of any remaining MM had succumbed to the severe drought in the Shenandoah Valley this summer and fall. One thing is for sure – the combined effort of participating groups in collaboration with the FS resulted in almost completely wiping out a major threat to forest health and biodiversity of the proposed SMNSA.

FOSM and our partners will monitor this site in the spring to see if new MM shoots are emerging. If we find any, we will organize a small group to take care of them. We now have 35 volunteers who can easily recognize it. We hope our continued monitoring and pulling will eventually eradicate MM from the Shenandoah Mountain area.

We are also seeing occurrences of Garlic mustard, Japanese stiltgrass, Ailanthus, Oriental lady’s thumb, and one small patch of Wavyleaf basketgrass along trails in the proposed SMNSA. PATC volunteers are increasingly incorporating control of non-native invasive plants into their trail maintenance and have attacked several of these unwanted plants. Trail maintainers are in a good position to identify new populations of NNIS and control them while they are still small.

Many of these NNIS are spread by trail users. Hikers, backpackers, trail maintainers, naturalists, hunters, and fishermen can all play a role in protecting our Wilderness and National Scenic Areas by observing, reporting, and banding together to be stewards of our protected areas, the very richest repositories of nature itself, so that Virginia’s tremendous biodiversity can thrive, and future generations can enjoy it as we have.

Rich Hole Wilderness

In each newsletter, we will highlight one of the 23 Wilderness areas (totaling 135,674 acres) and three National Scenic areas on the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, because these are some of the most scenic and biologically diverse places, with some of the best hiking and camping in the whole Commonwealth.

Just off I-64 near Lexington you’ll find the 6,532-acre Rich Hole Wilderness, designated in 1988. With three designated cold-water streams and a National Natural Landmark, this Wilderness is worth a visit. The North Branch and Alum Spring, both designated cold-water streams, separate the two major ridges of the Wilderness. Both ridges show evidence of the iron ore mining operations that occurred here in the late 1800s and early 1900s, for which the area is named. This area also harbors significant pockets of old growth. The Rich Hole Wilderness also contains a 1,300 acres National Park Service National Natural Landmark, one of ten in the Commonwealth. The Landmark contains an outstanding example of old growth cove hardwood forest with remarkably large oak and hickory trees.

There is one trail in the Rich Hole Wilderness, the Rich Hole Trail, which is one-way and around six miles in length. This trail is maintained by VWC Executive Director Mark Miller, with help from the Southern Appalachian Wilderness Stewards.

The Virginia Wilderness Additions Act, introduced into the Senate but not yet signed into law, will designate a new addition to the west of Rich Hole Wilderness. This 5,600-acre addition will create a nearly contiguous complex of 21,000 acres, making it the largest Wilderness on Virginia's National Forest.

Just off I-64 near Lexington you’ll find the 6,532-acre Rich Hole Wilderness, designated in 1988. With three designated cold-water streams and a National Natural Landmark, this Wilderness is worth a visit. The North Branch and Alum Spring, both designated cold-water streams, separate the two major ridges of the Wilderness. Both ridges show evidence of the iron ore mining operations that occurred here in the late 1800s and early 1900s, for which the area is named. This area also harbors significant pockets of old growth. The Rich Hole Wilderness also contains a 1,300 acres National Park Service National Natural Landmark, one of ten in the Commonwealth. The Landmark contains an outstanding example of old growth cove hardwood forest with remarkably large oak and hickory trees.

There is one trail in the Rich Hole Wilderness, the Rich Hole Trail, which is one-way and around six miles in length. This trail is maintained by VWC Executive Director Mark Miller, with help from the Southern Appalachian Wilderness Stewards.

The Virginia Wilderness Additions Act, introduced into the Senate but not yet signed into law, will designate a new addition to the west of Rich Hole Wilderness. This 5,600-acre addition will create a nearly contiguous complex of 21,000 acres, making it the largest Wilderness on Virginia's National Forest.

You can now support VWC every time you grocery shop! At no cost to you, Kroger will donate to VWC based on the shopping you do every day. Go to www.kroger.com/i/community/community-rewards and search for Virginia Wilderness Committee to add us to your account. Every time you swipe your card, you will help protect the wild public lands of Virginia that we all love and enjoy.